Our Story

Washington County, Virginia's story is one of frontier courage, cultural innovation, and steadfast community. Spanning from Native American habitation through pivotal moments in American history, its landscape and people have shaped, and been shaped by, centuries of dramatic change.

Washington County lies in the Ridge and Valley area of the Appalachia region. The valleys contain excellent farmland while forests cover the higher hills and mountains. Clinch Mountain rises to 4,689 feet while White Top Mountain reaches over a mile high at 5,525 feet. The county's three rivers, the North Fork, Middle Fork, and South Fork of the Holston River, have powered mills and sustained communities for centuries.

Historical Timeline

Journey through the centuries

10,000 BCE - 1700s

Pre-Colonial Era

Native American peoples, including the Cherokee, inhabited this region for millennia. Archaeological evidence shows human activity dating back 10,000 years, with sophisticated artifacts found throughout the area, especially along the Holston River valleys.

1747 - 1776

Colonial Settlement

European settlers, largely Scots-Irish and German, began arriving via the Great Wagon Road. The Wolf Hill Tract (now Abingdon) was surveyed in 1750. Permanent settlement began in 1769 after the French and Indian War.

December 1776

County Founded

Washington County was established—the second county in the US named for George Washington. The Overmountain Men from this region played a crucial role in the Battle of Kings Mountain (1780), a turning point in the Revolutionary War.

1800s

Growth & Education

Emory & Henry College founded (1836). The railroad arrived (1856), transforming trade and travel. The county became a center for education with multiple academies and colleges established.

1861 - 1865

Civil War Era

The county contributed soldiers to Confederate forces. General Stoneman's raid in December 1864 resulted in much of Abingdon being burned. The community faced devastation but rebuilt in the following years.

20th Century - Present

Modern Development

Damascus becomes a tourist destination with the Appalachian Trail and Creeper Trail. The county evolves from agricultural roots to a diverse economy including tourism, education, and healthcare.

Long before Europeans arrived, the land that became Washington County, Virginia, was home to a deep and continuous human presence extending back thousands of years. Archaeological findings reveal that prehistoric peoples inhabited the region for at least 10,000 years, with some evidence, such as the discovery of butchered mastodon bones near Plasterco, pointing to human activity up to 14,500 years ago. These early inhabitants lived along the fertile branches of the Holston River, where they established seasonal villages, raised crops, and hunted the rich game of the Appalachian foothills. By the time Europeans began to explore the area in the 16th and 17th centuries, however, no permanent Native settlements remained. The region appeared to be a borderland contested between the Cherokee to the south and the Shawnee to the north.

During the Late Woodland period, roughly 900 to 1600 CE, Native peoples in what is now Southwest Virginia lived in palisaded villages and practiced a sophisticated form of agriculture revolving around corn, beans, and squash. These communities were part of a larger network of trade and cultural exchange that connected the Monacan and other Siouan-speaking peoples of the Blue Ridge with the Cherokee and Iroquoian speakers farther south and west. Burial mounds and artifacts found in the region reflect a long tradition of craftsmanship, spirituality, and adaptation to the mountain environment.

The first Europeans to penetrate the region were likely Spanish explorers in the mid-16th century. Hernando Moyano, a lieutenant of Spanish conquistador Juan Pardo, led an expedition from Joara in present-day North Carolina around 1567 and attacked an Indigenous village known as Maniatique—believed by historians to have been near modern Saltville. Though archaeological evidence of this encounter remains inconclusive, the written records from the Spanish accounts suggest one of the earliest European incursions into the interior of the southern Appalachians.

In the early 18th century, as colonial Virginia expanded westward, the British Crown sought to secure the frontier through a network of settlements that would serve as a buffer between Indigenous nations and the coastal colonies. Major land grants were issued to encourage settlers, including William Patton's 100,000-acre Patton Grant and the Loyal (or Walker) Grant of 800,000 acres, both encompassing portions of present-day Washington County. One of the most significant of these tracts, the Wolf Hill survey of 1750, became the foundation for the modern town of Abingdon. Despite later myths linking Daniel Boone to its naming, records indicate that Boone did not visit the area until more than a decade later, in 1761.

Following the French and Indian War, migration into Southwest Virginia increased dramatically. Permanent settlement began around 1769, as families from Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley traveled southward along the Great Road, an early frontier route that roughly parallels today's Interstate 81. These settlers brought with them not only agricultural traditions and religious faith but also the spirit of independence that would soon define the region. Within a generation, their communities gave rise to forts, farms, and churches, laying the groundwork for the formation of Washington County in 1776, at the dawn of the American Revolution.

When the American Revolution erupted, the people of Washington County, Virginia, then part of Virginia's rugged frontier, overwhelmingly supported the Patriot cause. Yet, their primary concern during the early years of the war was not British troops, but rather the threat of attack from the Overhill Cherokee who occupied areas of present-day East Tennessee. Tensions between the two groups escalated after British agents encouraged the Cherokee to strike colonial settlements. In July 1776, a series of devastating raids forced hundreds of families to flee their homesteads and take refuge at fortified outposts such as Black's Fort in Abingdon, where several hundred people endured weeks of siege-like conditions. In response, Virginia militia forces launched a campaign that autumn, destroying multiple Cherokee towns and effectively crippling their ability to engage in large-scale resistance for the remainder of the conflict.

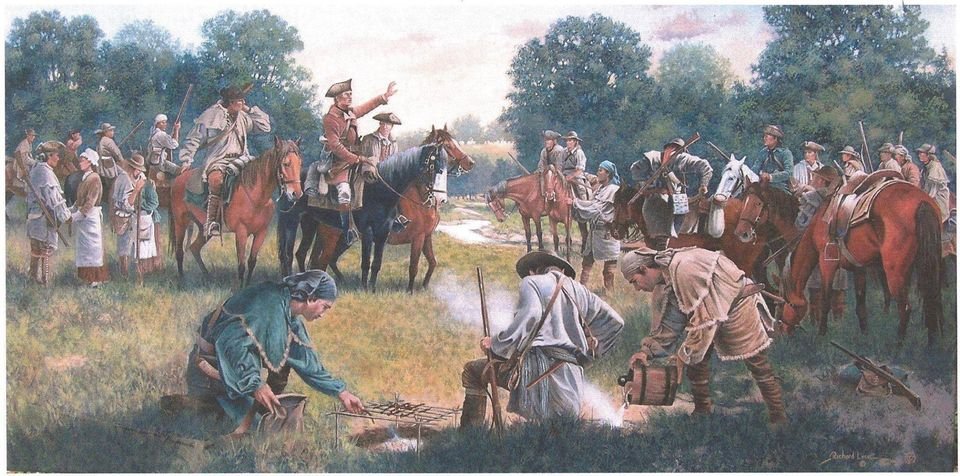

As the war shifted southward, Washington County's frontiersmen played a decisive role in one of the Revolution's most celebrated victories. In September 1780, Colonel William Campbell, often called the "bloody tyrant of Washington County" by Loyalists for his uncompromising leadership, gathered roughly 400 riflemen at the Abingdon Muster Grounds, then known as Craig's Meadow, to march against a British Loyalist force under Major Patrick Ferguson. Joined by militias from Southwest Virginia, what is now Tennessee, and the Carolinas, their group became famously known as the "Overmountain Men." They undertook a grueling 200-mile march across the Blue Ridge Mountains through rain and snow, often surviving on what they could forage, before uniting at Sycamore Shoals in modern Elizabethton, Tennessee.

On October 7, 1780, Campbell's force of frontier riflemen surrounded Ferguson's Loyalists atop King's Mountain in South Carolina. Within little more than an hour of furious fighting, the Patriots achieved one of the most complete victories of the Revolution: Ferguson was killed, nearly 300 Loyalists were slain, and more than 700 others surrendered. Washington County's soldiers, who had marched farther than any other contingent, suffered some of the heaviest casualties among the Patriot ranks. Thomas Jefferson later called the triumph at King's Mountain "the turn of the tide of success," acknowledging it as the pivotal moment that reversed British dominance in the Southern Campaign.

Campbell's leadership at King's Mountain cemented his reputation as a hero of the frontier, and his men returned home to a region forever proud of their role in securing independence. Today, the Abingdon Muster Grounds stand preserved as part of the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, commemorating the courage and endurance of those early Virginians who helped determine the fate of a nation from the far reaches of the Appalachian frontier.

When the Civil War began, Washington County, Virginia, found itself divided in sentiment but initially inclined toward preservation of the Union. Many residents valued the economic and cultural stability that connection offered. Yet, when President Abraham Lincoln issued his call for troops following the bombardment of Fort Sumter, opinions rapidly hardened. For most, loyalty shifted toward Virginia and the Confederacy. Within weeks, hundreds of local men volunteered for service, forming companies such as the Washington Mounted Rifles and enlisting in regiments like the 37th and 48th Virginia Infantry. These troops became part of the storied Army of Northern Virginia, serving under Generals Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson and Robert E. Lee in nearly every major campaign, from the Shenandoah Valley to Gettysburg and Cold Harbor.

The 37th Virginia Infantry, organized in Abingdon in May 1861, epitomized the courage and tragedy of Washington County's contribution. The regiment fought with distinction in Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign and endured staggering losses at battles such as Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. By the war's end, only two officers and thirty-nine men of the original 846 mustered survived to surrender at Appomattox. Their sacrifices reflected the devastating human toll that touched nearly every family in the county.

On the home front, the realities of war were harsh. Food shortages, inflation, and blockades brought grinding poverty. The Confederacy's salt production at Saltville, crucial for preserving food, made the region a prime military target. In December 1864, Union General George Stoneman led a sweeping raid through Southwest Virginia, intent on crippling Confederate supply lines. His cavalry destroyed the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad bridges, the critical lead mines at Wytheville, and torched facilities associated with the Salt Works. Much of Abingdon suffered in the raid, including homes, mills, and depots burned by advancing troops. The Saltville campaign also witnessed one of the war's darker incidents, the massacre of wounded Black Union soldiers by Confederate irregulars following the battle, a grim reminder of the war's racial brutality.

When peace arrived in 1865, Washington County faced the daunting task of rebuilding a shattered economy and wounded population. Agricultural recovery came slowly, aided by new access to rail transportation in the 1870s, which linked Abingdon to Bristol and beyond. The railroad revived commerce and opened markets for livestock, lumber, and manufactured goods, setting the stage for the county's industrial growth in the postwar decades.

Reconstruction politics further reshaped local identity. Disputes over Virginia's public debt and resentment toward wartime suffering fostered a political realignment. Unlike many parts of the former Confederacy, Washington County gradually developed into a Republican stronghold, partly due to its mountain culture and opposition to the old eastern elite. Demographically, enslaved African Americans had comprised about fifteen percent of the population before the war, laboring mainly on farms near Glade Spring, Abingdon, and Bristol. Emancipation brought both opportunity and hardship as freedmen navigated new forms of tenancy and labor, while institutions such as churches and schools became vital centers of Black community life. By the 1880s, the scars of battle had begun to fade, yet the memory of divided loyalties and sacrifice remained woven into Washington County's identity, a legacy of resilience forged in one of Virginia's most turbulent eras.

Washington County, Virginia, developed a distinguished reputation as one of the Commonwealth's most vibrant centers of education throughout the 19th century. The region became known not only for its commitment to quality schooling but also for the number and variety of institutions that flourished in its small towns, especially in Abingdon.

The earliest and most prominent of these was the Abingdon Male Academy, founded in 1802 with the support of salt entrepreneur William King, whose endowment of $10,000 helped establish the school on a hill overlooking the town. The academy became a respected preparatory institution, educating generations of young men in classical studies and moral instruction. It thrived through much of the 19th century, temporarily closing during the Civil War when it served as barracks and a makeshift hospital for Confederate troops. After the war, the building was rebuilt and continued in operation until 1905. When the trustees finally closed the academy, the property was leased to the town and later became home to William King High School and, eventually, the William King Museum of Art, preserving the educational spirit of the site.

Common schools in Washington County were likewise recognized as models of excellence throughout Virginia prior to the Civil War. The county's early adoption of state-supported, community-based education earned it the reputation for having the best public schools in the state at the time, reflecting a deep civic commitment to accessible learning.

Higher education in Abingdon expanded rapidly after the mid-19th century. The Holston Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, which also founded Emory and Henry College, opened Martha Washington College in 1860 in the grand home of General Francis Preston. The school served as a women's college, offering a curriculum emphasizing literature, sciences, and Christian education. Although legend suggests the building was used as a hospital during the Civil War, Martha Washington College operated continuously throughout the conflict, later merging with Emory and Henry College in 1919 before closing permanently in the 1930s. The former college building remains a local landmark as the Martha Washington Inn.

In 1867, the Roman Catholic Visitation Order established Villa Maria Academy, a distinguished girls' school that emphasized both spiritual formation and academic excellence. The following year, the Presbyterian Church founded the Stonewall Jackson Female Institute, providing another avenue for women's higher education in Abingdon's growing academic landscape. Together, these institutions underscored the county's diverse religious and cultural investment in learning. Although Villa Maria Academy relocated to Wytheville at the beginning of the 20th century and the Stonewall Jackson Institute closed during the Great Depression, their presence represented a golden age of education in postwar Southwest Virginia.

By the turn of the 20th century, Washington County's educational network, from its pioneering academies to its denominational colleges, had earned it lasting recognition as a cornerstone of intellectual life in the region. This legacy continued into the modern era with the establishment of Virginia Highlands Community College in 1967, ensuring that the county's longstanding dedication to learning endures well into the 21st century.

Emory & Henry University

Emory and Henry University, founded in 1836 under the auspices of the Holston Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, holds the distinction of being the oldest institution of higher learning in Southwest Virginia. Named in honor of Bishop John Emory, a respected Methodist leader, and Patrick Henry, a renowned patriot and orator, the university reflects a lasting commitment to both spiritual enrichment and active civic engagement. This founding vision has guided Emory & Henry throughout its long and storied history.

The university campus itself is a designated historic district listed on both the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Historic Landmarks Register, honoring its deep contributions to education in the rural mountain region. During the American Civil War, Emory & Henry's main administration building was repurposed as a Confederate hospital, playing a critical role in wartime care. The campus witnessed significant historical events, including tragic episodes involving wounded African American Union soldiers during the Battle of Saltville, underscoring its complex legacy.

In 1899, Emory & Henry made a transformative step toward inclusivity by enrolling women for the first time, progressively evolving into a fully coeducational institution over the following decades. The university also endured the hardships of the Great Depression, yet it emerged resiliently, experiencing growth fueled in part by enrollment of post-war veterans benefiting from the GI Bill. These veterans contributed to a flourishing campus expansion through the mid-20th century, laying the foundation for the modern university's facilities.

Today, Emory and Henry University proudly stands as one of the few Southern colleges that have continuously operated for nearly two centuries under their original name and religious affiliation. Its enduring heritage represents a profound blend of educational excellence, Methodist tradition, and regional significance, maintaining its role as a beacon of learning and service in Southwest Virginia.

Learn More About E&H HistoryAbingdon

County seat since 1778. Economic and political center. Home to three governors: Wyndham Robertson, David Campbell, and John Buchanan Floyd. The name likely comes from Abingdon, England.

Damascus

Developed with lumber industry (1906-1928). Now a tourist center where the Appalachian Trail and Creeper Trail intersect. Known as "Trail Town USA."

Glade Spring

Excellent farmland in the northeast. Close to Salt Works. Once hosted Washington Springs and Seven Springs resorts, believed to have curative waters.

Saltville

Rich archaeological site. First salt well dug in 1782. Preston and King families derived great wealth from salt extraction. Supplied much of the Confederacy's salt, leading to two battles in 1864.

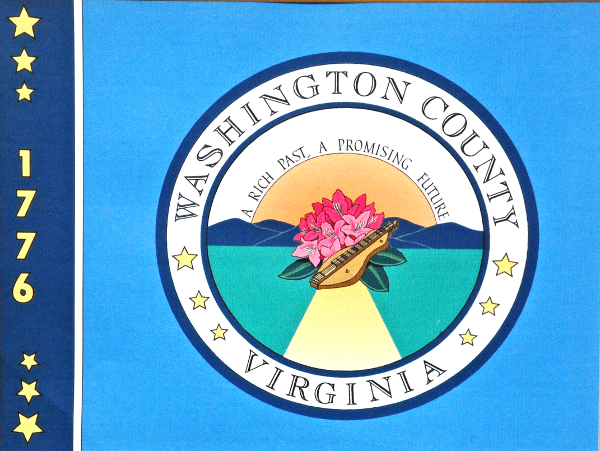

The emblems of Washington County, Virginia, reflect both its Revolutionary War origins and its enduring pride in history and heritage. The official Great Seal of Washington County was adopted by the Board of Supervisors on January 4, 1978. Designed by Arthur DuBois, the seal's central shield bears three stars and two horizontal bars, a design derived from the family crest of General George Washington, the county's namesake. This connection honors both Washington's leadership as Commander-in-Chief during the American Revolution and the county's founding the same year, 1776, a date proudly displayed on the seal.

Surrounding the shield is a circular border with the county's name and the year of establishment, symbolizing unity and continuity. The seal serves as the principal emblem of county government, appearing on official documents, signs, and the county courthouse. Its classical heraldic form pays homage to 18th-century American symbolism, which often drew upon coats of arms and republican ideals to express civic identity and public virtue.

Two decades after adopting the seal, the county introduced its official flag on July 14, 1998. Designed by Jennifer Holliday, the flag features a bold adaptation of the county's visual identity through the inclusion of a "Minor Seal." This secondary emblem centers on a laurel blossom and Appalachian dulcimer, two symbols deeply tied to Washington County's natural beauty and cultural traditions. Behind them rise stylized blue mountains, rolling green fields, and a radiant golden sun, evoking the geography and optimism of Southwest Virginia. Above and below this central motif appear the county's motto, "A Rich Past, A Promising Future," affirming its respect for history and confidence in the years ahead.

The year 1776, shared by both the Great Seal and the flag, serves as a unifying emblem of origin and purpose, marking Washington County's establishment amid the struggle for independence. Together, the seal and flag represent a thoughtful blend of heritage and aspiration, a tribute to the county's Revolutionary roots and a visual affirmation of its continued progress within the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Explore More History

Visit our research library to dive deeper into Washington County's fascinating past